Case study: Simple Game Engine

Published Feb 18, 2026

Written by

Dmytro K.

Introduction

Generally, game development requires competence in many different areas. Fore example, the creator has to handle game design, visual design, story, character development, and of course programming. SGE is a 2D game engine that covers the technical part of the process - the programming part.

Game engines, and games in general, are best developed using lower level programming languages. If the goal is performance (which it should be, because performance greatly impacts the experience and enjoyment of your games), the low level languages give access to system resources and memory management, which allows developers to better control how they write their programs.

For this particular engine C++ is used. C++ combines the benefits of low level memory access, lack of automatic memory management (which, at times, can be taxing on system resources), and convenient syntax for Object Oriented programming, and since C++ 11, even for Functoinal programming.

The engine is built in tandem with the SFML library, which provides convenient abstractions for media: sounds, keyboard inputs, system windows. This allows to focus on the core game engine development, with the lower level things already abstracted out, while still, at the same time, allowing the users of the game engine to code in C++ with its benefits.

Logical blocks

On the technical side, the game engine consists of 5 distinct blocks:

Each part defines a distinct logic block of the engine.

Logic: describes the core idea ad components of the game engine. Allows creation and management of game entities and their interactions, scenes, and animations.

Assets: describes assets management abstractions. Allows to conveniently load and manage textures, fonts, and sounds.

Controller: describes controller management abstractions. Allows to conveniently define controller interactions.

View: describes game camera management abstractions.

Debug: defines some abstractions that conveniently help debugging.

All parts are organized and managed in the main unit called Universe.

Core ideas

Everything is an Entity.

Its simple. Everything you see on the screen, at any given time is an Entity with certain properties assigned to it.

For example, to create a player on the screen, the Entity with Sprite, MotionUnit, CollisionShape, State, TextureSequence, objects can be created, but for the tiles that the player would stand on, the Entity with Sprite and CollisionShape is generally enough. In this way, this simple modular structure allows pretty straightforward development.

Structure

The main structural idea of how this engine works has come about as a result of refactoring, and I call it the Component - Manager architecture (CM). There are Components that describe some specific functionality, and there are corresponding Managers that manage how components are processed within the engine.

For example, EntityManager manages Entity objects, MotionUnitManager manages MotionUnit objects, etc.

Components and Managers can differ hierarchically. There are "Core components" which describe specific behaviour or feature, and there are "Higer-order components" which consist of, store, and organize core components. Thus, the Entity is a higher-order component, that can be built up using core components picked for a specific game object needs. Similarly, EntityManager eases the management of Entity sub-components by automatically employing and organizing corresponding core managers.

Consequently every manager is managed by the "Main manager" called Universe.

Game loop

The main manager Universe constantly runs the game loop, in which the "Managers" of the engine are constantly processing corresponding components in a specific order.

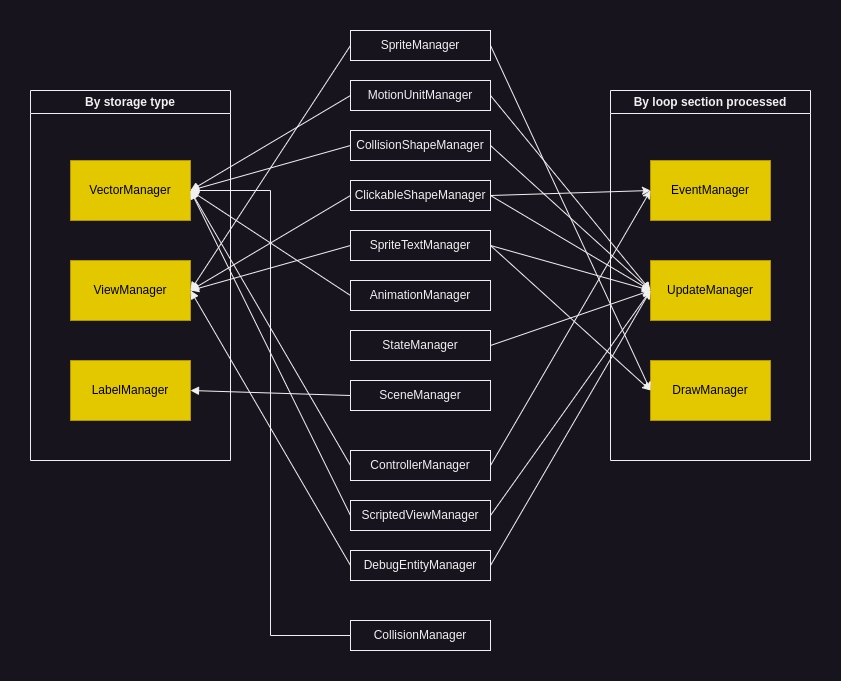

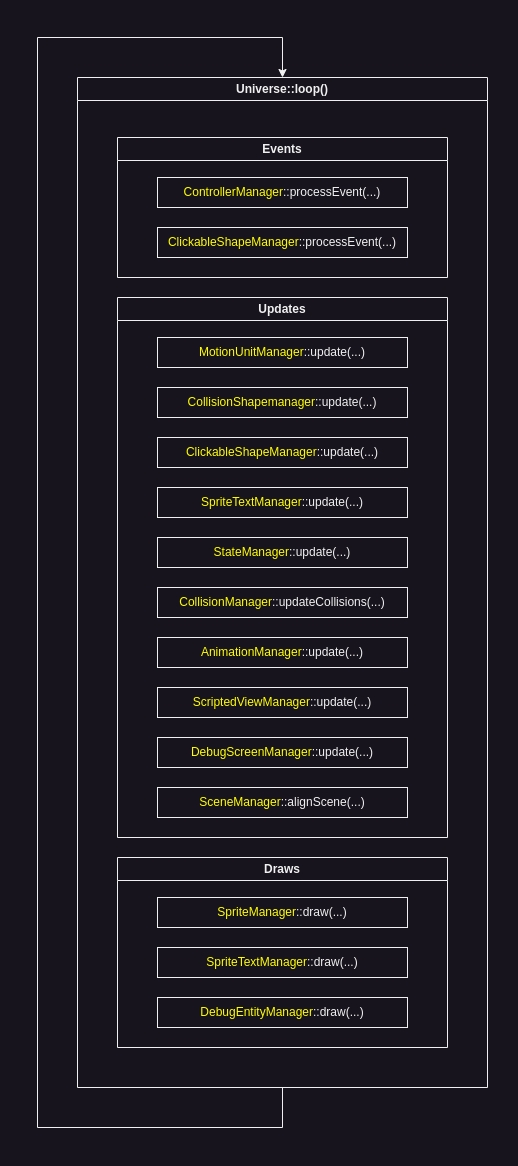

The loop consists of 3 processing sections: "Event", "Update", "Draw". Programmatically, each manager is processed in the corresponding section:

For convenience, managers are also organized by their storage type.

Additionally components can be in one of 3 states: "active", "paused", and "hidden", which allows developers to control the behaviour of the component, on the fly.

For example, as you can see, "active" components are always processed, "paused" are only drawn, and "hidden", are neither processed nor displayed.

The components are processed in a specific sequence:

If you think about it, it makes sense: Controller events should be processed first, because user triggered events may impact all further calculations; MotionUnits should be updated first, as the physics, that they calculate, may impact Collisions, States, and Animations (in this sequence); which furthermore impacts what is actually drawn on the screen.

This results in architecture that is fairly easy to understand, and programmatically simple to use. Everything is clean and organized.

The simplest, basic usage example could look like this:

#include <SFML/Graphics.hpp>

#include <SFML/Audio.hpp>

#include "SGE.hpp"

int main(){

sf::RenderWindow* window = new sf::RenderWindow(sf::VideoMode(1000, 600), "Test");

sge::Universe* universe = new sge::Universe(window);

// Your game code

universe->loop();

return 0;

}Possibilities

The modular architecture, and features of SGE allow to handle common game development tasks.

Camera & Views

The beauty is in the details. Subtle improvements like texture particles, or smooth camera movement greatly enhances game experience.

The ScriptedView allows developers to easily setup the game view and create smooth camera movement that gradually catches up to the player. For instance:

class CameraView : public sge::ScriptedView{

public:

CameraView(sge::Entity* playerEntity) : m_playerEntityPtr(playerEntity){

this->setCenter(sf::Vector2f(100, 100));

this->setSize(sf::Vector2f(500, 300));

};

void script(){

sf::Vector2f center = m_playerEntityPtr->sprite->getPosition();

center.x += 4;

center.y += 4;

m_scroll.x = center.x - this->getCenter().x - m_scroll.x / 100;

m_scroll.y = center.y - this->getCenter().y - m_scroll.y / 100;

this->setCenter(center - m_scroll);

}

private:

sf::Vector2f m_scroll = sf::Vector2f(0, 0);

sge::Entity* m_playerEntityPtr;

};This class creates the desired effect:

It's barely noticable, yet still plays its part.

Collisions

Another problem that developers have to solve, when developing games, is Collision handling. A collision occurs when 2 or more objects intersect with each other. Then, for example when player object collides with the ground tile, the appropriate response should be executed, that creates the effect of character "standing" on the tiles.

During the development of SGE, I have came up with the concept of "collision phase", that allows to reason about, and control collision responses throug time.

The collision, when registered, can be in any of 3 collision phases: "continuous", "start", "end". Every game loop iteration, all collisions get registered, and their phase determined by use of set theory:

Internally, the CollisionManager keeps track of all present and past collisions, and then, programmatically the phase is determined simply through calculating collision vector's intersections and differences:

...

std::sort(presentCollisions.begin(), presentCollisions.end());

std::sort(pastCollisions.begin(), pastCollisions.end());

std::vector<sge::Collision> continuousPhaseCollisions;

std::set_intersection(

pastCollisions.begin(),pastCollisions.end(),

presentCollisions.begin(),presentCollisions.end(),

std::back_inserter(continuousPhaseCollisions)

);

std::vector<sge::Collision> startPhaseCollisions;

std::set_difference(

presentCollisions.begin(),presentCollisions.end(),

continuousPhaseCollisions.begin(),continuousPhaseCollisions.end(),

std::back_inserter(startPhaseCollisions)

);

std::vector<sge::Collision> endPhaseCollisions;

std::set_difference(

pastCollisions.begin(),pastCollisions.end(),

continuousPhaseCollisions.begin(),continuousPhaseCollisions.end(),

std::back_inserter(endPhaseCollisions)

);

...Then, the game developer, who is using the engine, can assign components to collision groups, and write specific interactions between the objects in said groups, based on the collision phase.

For example:

class PlayerSurfaceInteraction : public sge::CollisionInteraction{

public:

PlayerSurfaceInteraction(std::vector<std::string> initiatorGroups, std::vector<std::string> recipientGroups) : sge::CollisionInteraction(initiatorGroups, recipientGroups){};

bool collisionDetectionAlgorithm(sge::CollisionShape* initiator, sge::CollisionShape* recipient) override{ return sge::boundingBox(initiator, recipient); }

void startPhaseCollisionResponse(std::vector<sge::Collision> collisions) override{

sge::StateCluster* playerStateCluster = collisions[0].initiator->getOwnerEntity()->stateCluster;

playerStateCluster->deactivateState("jump");

playerStateCluster->activateState("on_ground");

}

};Then, setting up the interaction in main:

universe->collisionManager->registerComponent(new PlayerSurfaceInteraction({"player"}, {"tiles", "box"}));Visually:

And, for example, an interaction with the "Box":

Here, for example, the interaction algorithm is:

collision player x box:

phase start - paint box border red

phase continuous - add velocity to box in the direction of player movement

phase end - gradually remove velocity, paint box border greenPhysics

This brings us to another feature that SGE allows developers to create: physical phenomena such as gravity, friction force, and potentially other.

In the example above, you can observe how the box, instead of abruptly stopping on interaction end, gradually slides, and then stops. In short, the MotionUnit object of the Entity allows developers to assign different "forces" to the objects, and create calculation scripts with or between them.

For example:

class BoxSurfaceInteraction : public sge::CollisionInteraction{

public:

BoxSurfaceInteraction(std::vector<std::string> initiatorGroups, std::vector<std::string> recipientGroups) : sge::CollisionInteraction(initiatorGroups, recipientGroups){};

bool collisionDetectionAlgorithm(sge::CollisionShape* initiator, sge::CollisionShape* recipient) override{ return sge::boundingBox(initiator, recipient); }

void continuousPhaseCollisionResponse(std::vector<sge::Collision> collisions) override{

sge::MotionUnit* boxMotionUnit = collisions[0].initiator->getOwnerEntity()->motionUnit;

if(boxMotionUnit->velocity.x){

if(boxMotionUnit->velocity.x > 0){

boxMotionUnit->contactForces["kinetic_friction"] = sf::Vector2f(-200, 0);

}

else if(boxMotionUnit->velocity.x < 0){

boxMotionUnit->contactForces["kinetic_friction"] = sf::Vector2f(200, 0);

}

}

else if(!boxMotionUnit->velocity.x){

boxMotionUnit->contactForces.erase("kinetic_friction");

// static friction, for example

}

}

void endPhaseCollisionResponse(std::vector<sge::Collision> collisions) override{

sge::MotionUnit* boxMotionUnit = collisions[0].initiator->getOwnerEntity()->motionUnit;

boxMotionUnit->contactForces.erase("kinetic_friction");

}

};And visually:

The box gradually slides, when touching ground tiles.

You can observe the states and forces displayed conveniently bu use of the DebugEntities.

Conclusions

Game development requires knowledge and expertise in many different spheres of development and design. SGE provides convenient tools and abstractions that ease the programming part of the process. Use it as an inspiration, or directly for your games, if you like.